Where Does the Money for Schools Come From

In every state, funding for public education comes from a combination of local and state taxes, plus some federal money. The mix varies a bit from one state to another, and it can change over time. Where does the money come from?

In This Lesson

Do property taxes pay for schools in California?

How are public schools funded in California?

How much federal money pays for education in California?

How much does California's lottery help public schools?

Can school districts in California set property tax rates?

Where does funding come from for public schools?

What is Serrano v Priest?

Why are property tax rates the same everywhere in California?

What was Proposition 13?

What do property taxes pay for?

What is a Basic Aid district?

Why are California budgets so volatile and uncertain?

What is Prop 2?

★ Discussion Guide

Let's dispense with the smallish part first: As Ed100 Lesson 7.2 already explained, the federal government usually plays a pretty minor role in funding for K-12 schools. In normal times, federal funds cover less than a tenth of total K-12 expenditures in California, and most of the money is allocated to school districts on the basis of formulas. In times of fiscal crisis such as the Great Recession or the COVID-19 Pandemic, however, temporary federal support is crucial because the federal government can run a deficit. The state cannot.

Most of the money for public education comes from two big sources: state income taxes and property taxes — in that order. These taxes power the education system, but they also power many other functions of government. It's helpful to put the big picture in context.

California's three-part tax system

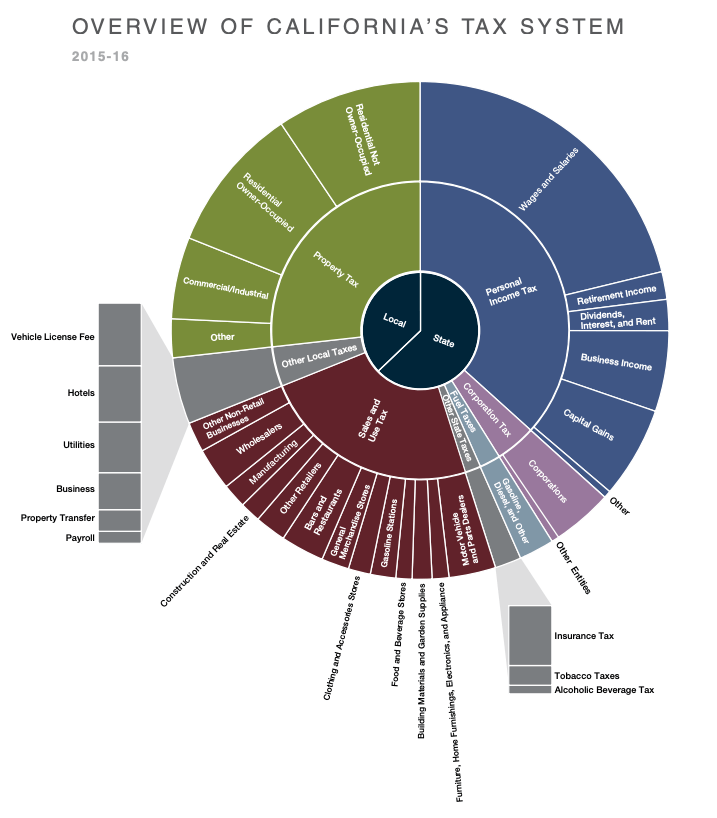

California's overall tax system consists of three roughly equal parts: personal income tax, property tax, and sales and use taxes. Education is funded by a mix of these sources, especially the first two. The schematic diagram below, from the California Legislative Analyst Office (LAO), summarizes the major sources and uses of funds.

Budgets are the complex, messy output of a political system. There is not a clear, easy-to-describe mechanism that determines which taxes are collected (revenue) and the purpose toward which they are allocated (expenditures). Income taxes, for example, support both school systems and municipal functions. The same is true of property taxes.

Sources of funds for public education in California

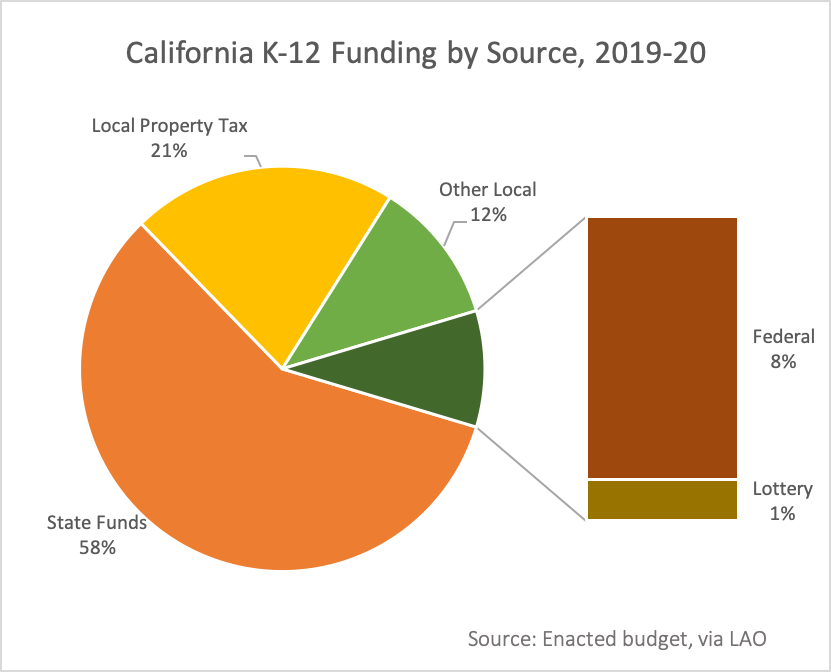

The chart below summarizes the main sources of general operating money for K-12 education in California using the 2019-20 budget as an example of a "normal" year. The relative size of the slices of the pie don't tend to change radically from year to year except in times of crisis, when federal funding might temporarily increase. The rest of this lesson examines each education-related slice of the pie more deeply.

How much do schools get from property taxes?

Historically, throughout the United States the cost of operating local schools was substantially covered by local property taxes. Today, these taxes are a significantly smaller share of the pie. In California, only a quarter of the operational funding of K-12 schools comes from property taxes. Counties play a key role in divvying up property tax revenue among the many agencies that rely on it. It can get messy. For example, schools have not always received their due slice of property taxes, a topic the Newsom administration promised to examine in 2021. It's a weedy issue, but if you feel like following it look for news about Educational Revenue Augmentation Funds (ERAF).

How much do schools get from state income taxes?

The biggest source of revenue for schools in California is state income taxes. This has been true since the late 1970s, after the passage of Proposition 13.

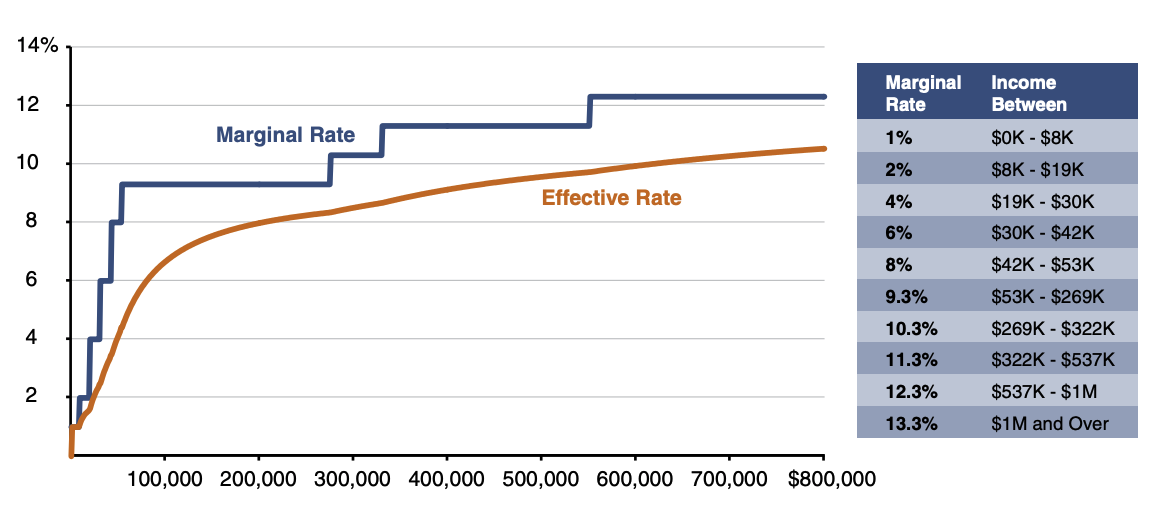

This may seem obvious, but income taxes are paid by people who have income. The majority of Californians pay little or no state income tax. California's income tax system is progressively indexed into nine tax brackets, which means that larger incomes are taxed at higher rates than smaller ones. California's top marginal income tax rate, 13.3%, is paid by about 90,000 of the state's top earners on the portion of their income above $1 million in a year.

About half of California's income taxes each year are collected from that year's biggest income earners — the top 1%. In 2016, California collected over $1 billion in taxes from individuals in a single zip code in Palo Alto. (Check your zip code using the CalMatters map How Much Do Your Neighbors Pay in California Taxes?)

How much do California schools get from the lottery?

California voters created the State Lottery in 1984. It's a big operation with about a thousand employees and a substantial marketing presence. About half of all adults in California buy at least one lottery ticket each year, knowing that — win or lose — a portion of the price of the ticket goes to support California's public K-12 schools and colleges.

Because the lottery is well-marketed, it's easy to overestimate its role in funding education. After prizes and expenses, the lottery pays for about 1% of the California education budget, equivalent to about $200 per student.

How much do California schools get from other local funds?

The Other Local slice, about 12% of the funding pie, is generated and controlled by local school districts. This sliver includes interest income, income from leasing out unused property, oil and gas wells on school district property (yes, really), parcel tax proceeds, donations, and a salad of other miscellaneous sources. [5] (You can find your district's sources of revenue in the District Financial Reports on the Ed-Data website.)

With rare exceptions, the state apportions education dollars to districts based on a calculation known as the Local Control Funding Formula, explained in Ed100 Lesson 8.5.

In a moment, we'll examine how California's education funding system evolved to its current form. But first, a quick recap:

| California's funding system for school operations | |

|---|---|

| Income taxes | The biggest source. The state's education system relies heavily on wealthy individuals making money and paying a lot of taxes. |

| Property taxes | Important, but rarely sufficient to fund the cost of local schools. |

| Federal funds | Generally provide less than a tenth of the money for public education, except in times of crisis. |

| Other local sources | Vary a lot, and we'll cover some of them in Lessons 8.9 and 8.10. |

| The Lottery | Raises about 1% of the budget for public schools. |

| LCFF | The Local Control Funding Formula determines how much your school district actually gets from the state. (Consider this foreshadowing. We'll explain it in Lesson 8.5) |

How did California end up with this approach to funding K-12 education?

The Courts and Voters Put the State In Charge

The source of funds for schools in California changed dramatically in the late 1970s. (chart data)

Until the late 1970's, California, like most states, funded its schools through local property taxes levied at rates set by local school boards. The amount raised for local schools varied a lot, depending on the local tax rate and the assessed value of local homes and commercial properties. County assessors held the important job of determining the taxable value of each property.

This arrangement was great for property-rich districts, but rotten for communities with low assessed values and lots of students.

This arrangement was great for property-rich districts, but rotten for communities with low assessed values and/or lots of students. Those communities had to set very high property tax rate to provide schools with as much money per student as their more fortunate counterparts. Serrano v Priest, the first in a series of landmark court decisions, challenged this arrangement in 1971. Is it really fair, the case asked, that some districts can tax themselves at a lower level and still enjoy more funding per student than others? After all, kids have no say in the wealth of their parents. The case led to court-mandated revenue limits, which were meant to equalize funding per student at the district level over time.

Voters passed Proposition 13 in 1978. Among other things, the proposition amended the state Constitution to set a limit on property tax rates at 1% of assessed value. The measure removed the power of school boards to levy local property taxes for local schools. To prevent education funding from plummeting, the state legislature stepped in, allocating state funds from a budget surplus to protect schools from what would have otherwise been massive cuts.

Suddenly, school districts had no local control over the amount of money available to fund their schools. Among the unintended consequences of Proposition 13, it centralized power over the education system in Sacramento. The state legislature and the governor became responsible for determining how funding would be distributed to districts. School boards, once powerful and independent, were left with the narrower job of playing the hand dealt to them by the state.

Another provision of Proposition 13 insulated property owners from higher taxes by freezing assessed values, allowing them to rise at a maximum annual rate of 2% regardless of their market value. (For more on Proposition 13, continue on to Lesson 8.4.)

Politics shifted along with funding control

Public schools in California are often thought of as local schools, but in many ways it has become more accurate to think of them as state schools. As discussed in Lesson 7.1, it is the state that bears the constitutional responsibility for public education, not school districts.

The old system was nuts.

Until 2013-14, education finance policies apportioned funds to districts based on a bizarre system of revenue limits. If you have a masochistic interest in California's historical school finance laws, knock yourself out. If not, better to spend your time understanding the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), explained in Lesson 8.5. It's a simpler and fairer system that replaced the rusty old plumbing of revenue limits and categorical funds.

Nowadays virtually all school districts in California rely on state funding, because local property taxes are insufficient to generate funding at the base level per student guaranteed by the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). (More about LCFF in Lesson 8.5.)

There are some exceptions. For example, if the boundaries of a school district include valuable commercial property, the property taxes generated are sometimes enough to fund the district beyond the base level. In 2014-15 about 100 of California's nearly 1,000 districts had the local capacity to fund their schools without state assistance. In California education jargon, these are officially known as community funded districts. (For historical reasons they are also inaccurately referred to as basic aid districts. For more on these districts, see Lesson 8.5.)

The role of political will in school funding

Nobody likes paying taxes. Passing a tax measure requires political will — a level of collective agreement that can overcome apathy, distrust, and competing priorities. It requires trust, too — not just that the money to be raised is needed, but that it will be spent well and make a difference. There are all kinds of reasons to say no.

Most voters are more inclined to support taxes that benefit their local community schools than ones that apply to the whole state of California. This is a big, diverse state. It is hard for voters to trust that decisions made in far-off Sacramento will really benefit families locally.

Serrano and Proposition 13 flipped California's education funding system from a local system reliant on local property taxes to a state system reliant on state income taxes. It made the system fairer, but it also made the system more politically distant. The old system was unacceptably inequitable, but in aggregate it was better at raising funds. Concerns about inadequate school funding started almost immediately after Proposition 13 was passed.

Income tax revenues are volatile

As discussed above, Proposition 13 triggered a big switch in the source of funding for public education from property taxes to income taxes. This shift brought a new challenge to California school budgeting: volatility.

Property values (and therefore property tax receipts) vary with the economic cycle, but they don't tend to change massively. Income taxes, by contrast, are very exposed to the booms and busts of the stock market. The individuals in the top 1% of income earners in California each year generate around 40% of the state's income taxes. Individual fortunes can change a lot from year to year, but they tend to have something in common: the stock market.

To smooth out some of the effects of the high volatility in state revenues, in 2014 California voters passed Proposition 2, which requires the state to spend a minimum amount each year to pay down its debts. The proposition also changed the rules for the state's rainy-day fund, an amount the state puts into a budget reserve to protect against years when revenues fall.

Keeping reserves is politically difficult. There are always real needs and worthy investments — and if a district builds significant savings it carries the risk of becoming a lucrative target for a lawsuit.

For people interested in funding for their local schools, the most important thing to know about California's system is that it can be terribly fickle. Education is an important priority, but not the only one. Especially in a stock market swoon, funding for schools cannot be assumed safe.

The next lesson, Lesson 8.4, focuses on the two measures that have had the biggest impact on education funding in California: Proposition 13 and Prop 98. Beginning in Lesson 8.5, this chapter explains the allocation process, especially including how the state determines the amount each school district receives under the rules of the Local Control Funding Formula.

Updated August 2017.

Updated October 2017.

Updated July 2018.

Updated May 2019.

Updated November 2019

Updated January 2021.

Where Does the Money for Schools Come From

Source: https://ed100.org/lessons/whopays

0 Response to "Where Does the Money for Schools Come From"

Post a Comment